The History of the Housing Struggle in Canada

This article recounts the history of the ongoing housing crisis in Canada to understand how working-class people have organized in the past and how we can apply these lessons to our current struggle.

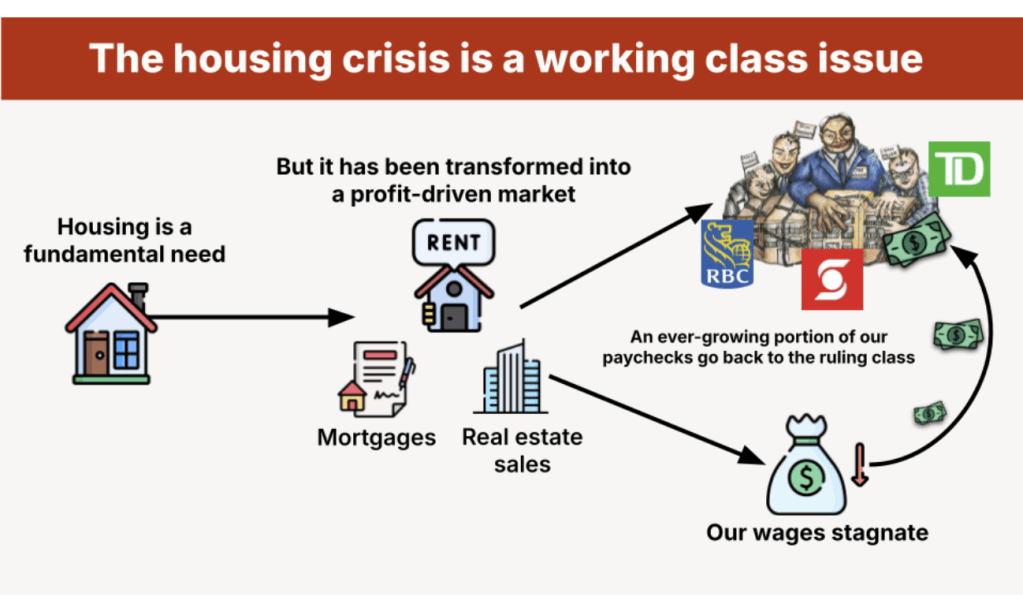

The Housing Crisis Is a Working-Class Issue

The ruling class, composed of corporate landlords, developers, banks, and the government that serves them, has transformed housing into a profit-driven market. Amassing wealth from our rent, mortgages, and the selling of real estate, an ever-growing portion of our paychecks are transferred back to this parasitic class’ pockets.

Today, roughly 10% of Canadians experience chronic, unstable housing, and almost 44% of Canadians are highly concerned about their ability to afford housing (Stat Can, 2021). But the current housing crisis is not new 一 it is the result of deliberate, profit-driven policies implemented over Canada’s history.

Caption: An acute housing shortage referenced in a 1950’s Toronto Star Article

Throughout Canada’s history, the ruling class have evolved their tactics to increasingly profit from housing, but the working class has continuously fought back. Many housing rights that we have today, such as rent control, were fought for and won by people getting together to organize.

Learning from the 1970s Housing Struggles

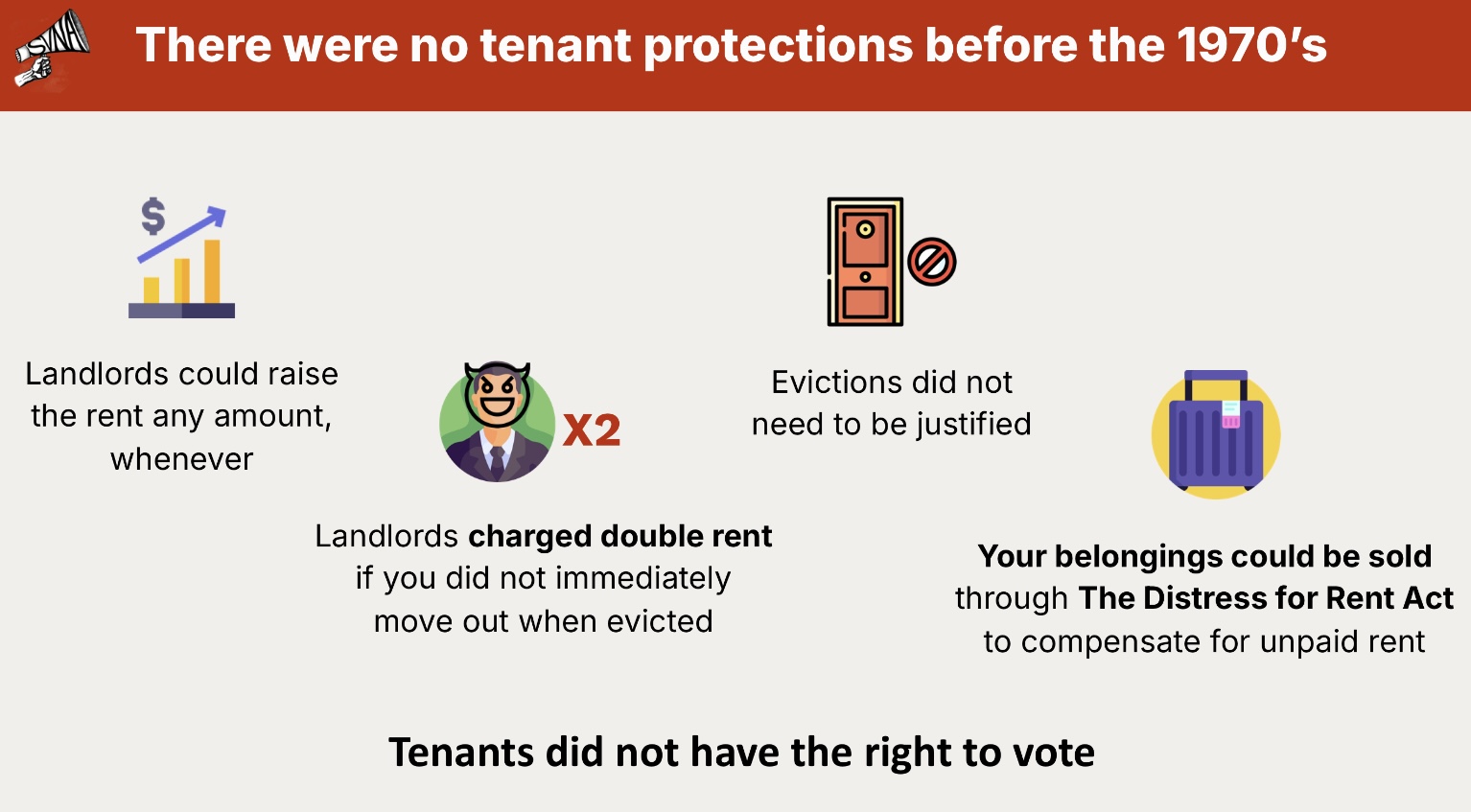

Before the 1970s, tenants in British Columbia (BC) had no legal protections. The Landlord and Tenant Act of 1897, copied from English Common Law, only concerned the rights of landlords.

50 years later, the National Housing Act of 1938 was created with only one requirement concerning renters: landlords had to provide “sanitary” housing.

Landlords could charge double rent if the tenant did not immediately move out when evicted and sell tenants’ belongings through The Distress for Rent Act to compensate themselves for unpaid rent. Moreover, tenants did not have the right to vote in municipal elections.

Things began to change in 1968 when 75 tenants got together in the Kitsilano neighbourhood to fight against a 5% rent increase in an apartment building owned by a major Canadian realtor at the time: Block Brothers.

Block Brothers won this fight, but the tenants reacted to this loss with a new resolve to try again. A few months later, when another building faced a rent increase, the tenants prepared a set of demands and committed to not pay rent until the demands were met.

The tenants’ demands were:

- Limit rent increases to once a year

- Provide eviction orders at a minimum of 3-months prior, and

- Allow interest to be earned on security deposits

These demands were won in Vancouver.

This successful fight led to the biggest meeting of tenants ever held in Vancouver: 750 tenants gathered and created the Vancouver Tenants Council. They planned to establish ‘tenant committees’ in every apartment building to strengthen protection for all tenants.

The next year, the Vancouver Tenants Council campaigned for the right of tenants to vote in civic elections, for enforcement of the building code, and for landlords to justify evictions.

Such big demands forced the City of Vancouver to create the Vancouver Rental Accommodation Grievance Board.

This victory led to increased tenant confidence and they decided to fight for Vacancy Control. Vacancy control is vital for renters as it prevents landlords from increasing rents between different tenants.

To achieve Vacancy Control, tenants collectively withheld their rent payments. One of these rent strikes, five-month long, tragically ended with 25 evictions. But, by 1972, the tenants won Vacancy Control legislation. It was a major victory against the landlord class fighting tooth and nail against it.

The next tenant demand focused on the amount of the yearly rent increases. In 1973, yet another battle began in response to a 25% rent increase in another building owned by Block Brothers.

A special meeting was called to resolve the tenants’ complaints. Over 700 people attended, both tenants and landlords. The landlords put on a fierce fight to justify their cause and they were openly supported by the Mayor of Vancouver.

In spite of that, the tenants kept organizing. They presented a petition with 25,000 names to the Province which intervened by taking the matter out of the hands of landlords and placed it before a newly created Rent Review Commission. Through the Rent Review Commission, tenants across B.C. won the capping of rent increases to the rate of inflation.

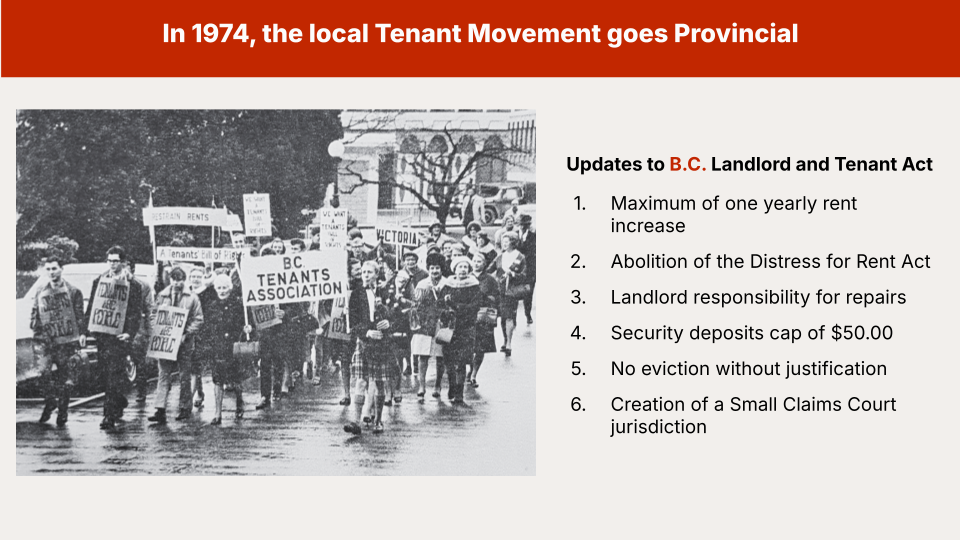

This win empowered organized tenants to demand and obtain the updating of the old Landlord and Tenant Act of 1938 to guarantee the following rights for all of British Columbia renters:

- No more than 1 rent increase per year, linked to inflation

- Abolition of the Distress for rent Act

- Landlord responsibility for repairs

- No eviction without justification

- Establishment of a Small Claims Court

This was a breakthrough for the newly formed B.C. tenant movement born from years of struggle in Vancouver.

After all these wins, why are we in such a bad situation as working class people who rent today? On the renters side of the struggle, the Vancouver Tenant Council’s plan to form defence committees in every building failed — they dissolved when their short term issues were resolved. On the landlord side, they successfully lobbied for the reversal of vacancy control legislation in a matter of a few years. Without vacancy control, rent will always increase.

It is in this challenging climate that individual and mass evictions have since become the new normal.

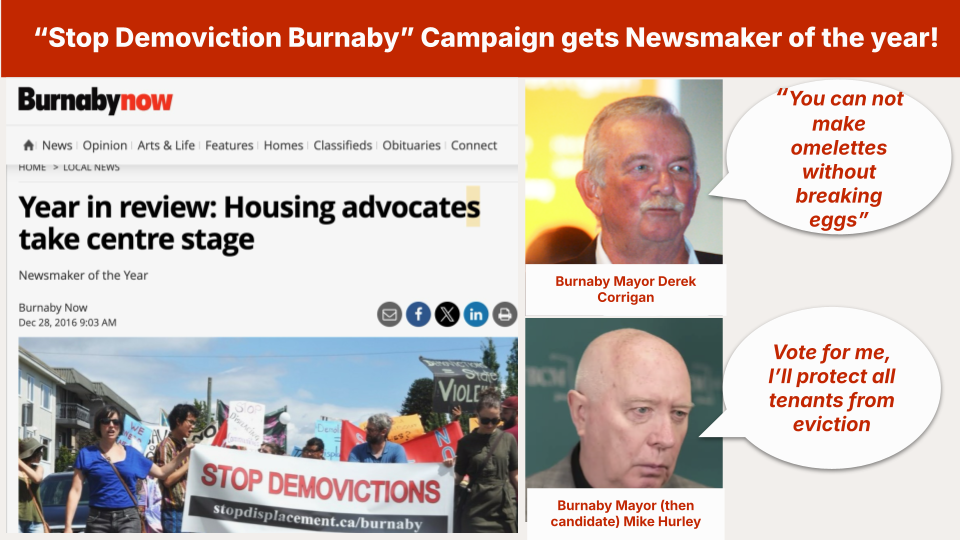

The Burnaby Campaign

In 2015, The Alliance Against Displacement (AAD), a new group with roots in the defeat of several long campaigns to get the government to build social housing, began organizing in Metrotown. They wanted to resist the planned mass displacement of renters and expose the need for affordable housing everywhere in BC.

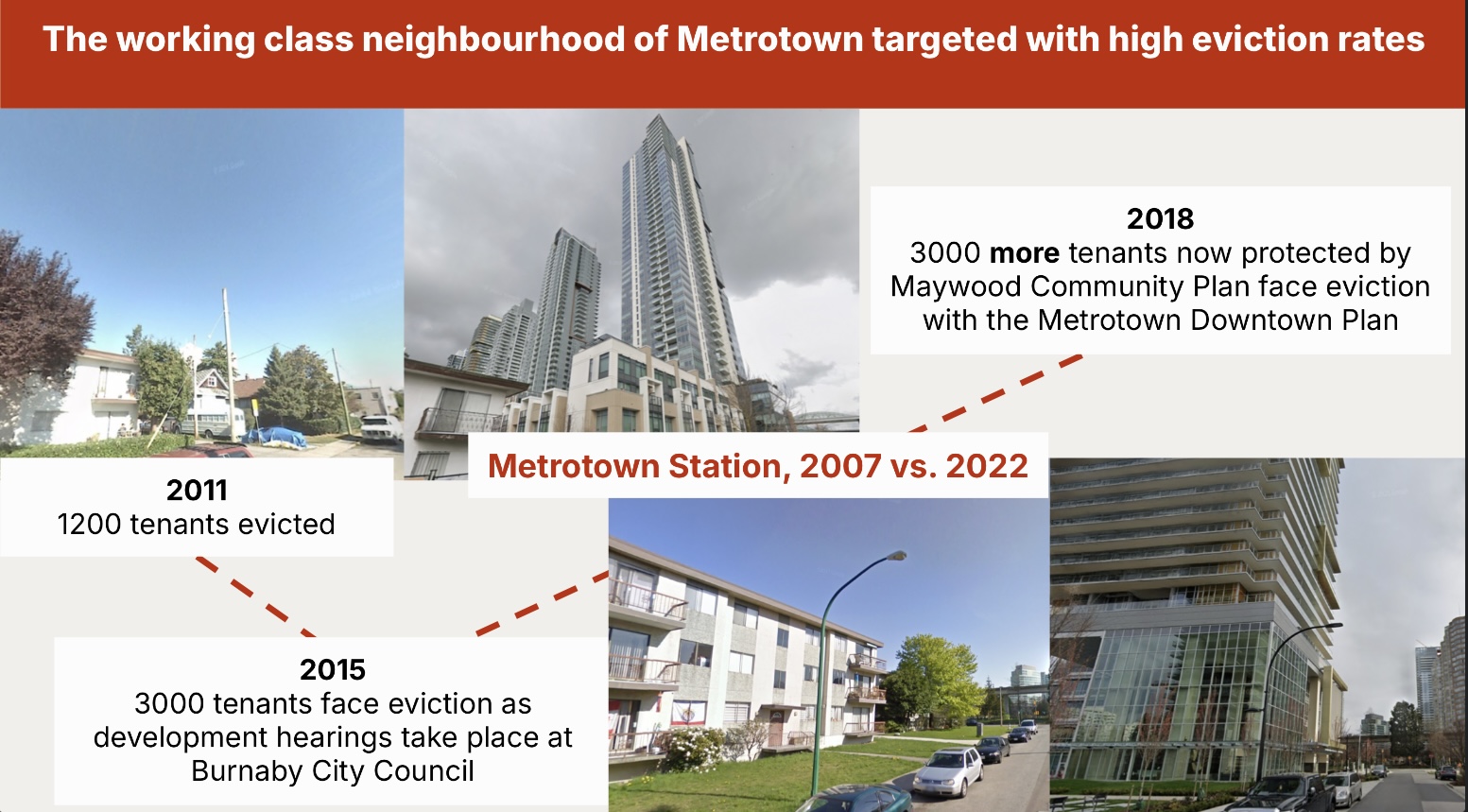

Metrotown was one of the last large working class neighborhoods in the lower mainland. Dozens of aging low-rise apartment buildings provided affordable rents to over 10,000 renters with shopping, schools, a community centre and a convenient location near the skytrain station.

By 2011, 1200 tenants had already been evicted and by 2015, 3000 more were threatened by ongoing development permit hearings taking place at Burnaby City Council.

In addition to these one off hearings, council was in the process of replacing the Maywood Neighbourhood Plan, which specifically protected 3000 additional tenants from being displaced, with a new plan, the Metrotown Downtown Plan, that would replace every existing apartment with luxury towers.

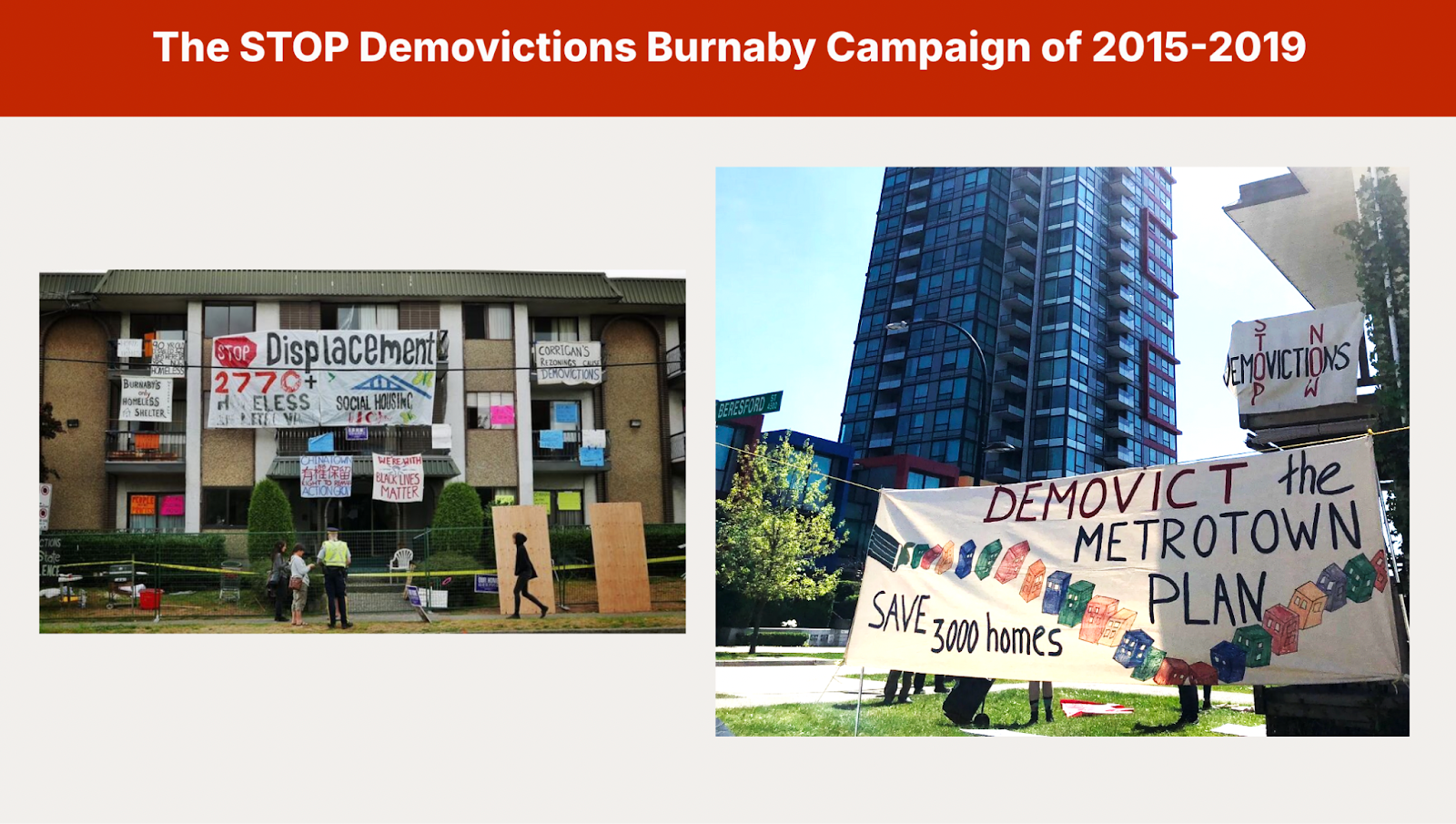

AAD organized door-knocking, community meetings, postering, and leafleting, leading to the formation of the Stop Demovictions Burnaby Campaign.

By 2016, members of the campaign occupied an apartment building recently bought and demovicted to publicize the struggle. The “squat” lasted 12 days ending with a police take-down but it did put the tenant’s plight on the forefront of the news and in the crosshairs of the reelection campaign of mayor Derek Corrigan.

The Stop Demovictions Burnaby Campaign produced and published an alternative to the Metrotown Downtown Plan called The People’s Plan for Development without Displacement.

The People’s plan was presented to the mayor and council multiple times in the summer of 2017 by multiple affected tenants and organizers.

The People’s Plan lost to the Metrotown Downtown Plan at City Council that fall. Thousands of tenants were forced to live under the threat of looming eviction from their affordable neighbourhood. In the face of this loss, Stop Demovictions Burnaby kept organizing, with the hope of supporting tenants resisting eviction. Applications to the Residential Tenancy Board were used to gain time, tenants and organizers occupied the Mayor’s office as well as that of MLA, Anne Kang. Tenants rallied and marched and kept up all the organizing tactics mentioned earlier in order to increase mass support.

By 2018, tenant evictions were on Burnaby citizens’ minds and on every politician’s radar. Popular support was evident, Stop Demoviction Burnaby was named newsmaker of the year. Pro-development Mayor Corrigan was broadly disparaged for callously proclaiming “you can not make omelettes without breaking eggs”. His opponent Mike Hurley used the issue to win the election with a promise to protect all Burnaby renters starting with a 6 month moratorium on evictions.

But, he did not follow through on his promises. Instead he negotiated a “Tenant Assistance Policy” (TAP) advertising it as “the best tenant protection in Canada”. The weak promises of the TAP are meant to hide the destruction of an affordable neighbourhood. While it claims to offer relocation assistance and the right to return to the new building with financial subsidies, developers can by-pass the TAP’s obligations through legal and illegal means. Ultimately, only a handful of evicted tenants end up returning and the rent goes back up when a new tenant moves in.

Reflecting on the Battle of Metrotown provides us with many lessons through each one of its many twists and turns: it won a tenant protection legislation but lost the battle to stay in their neighborhood and no social housing policies of any significance have appeared to this day.

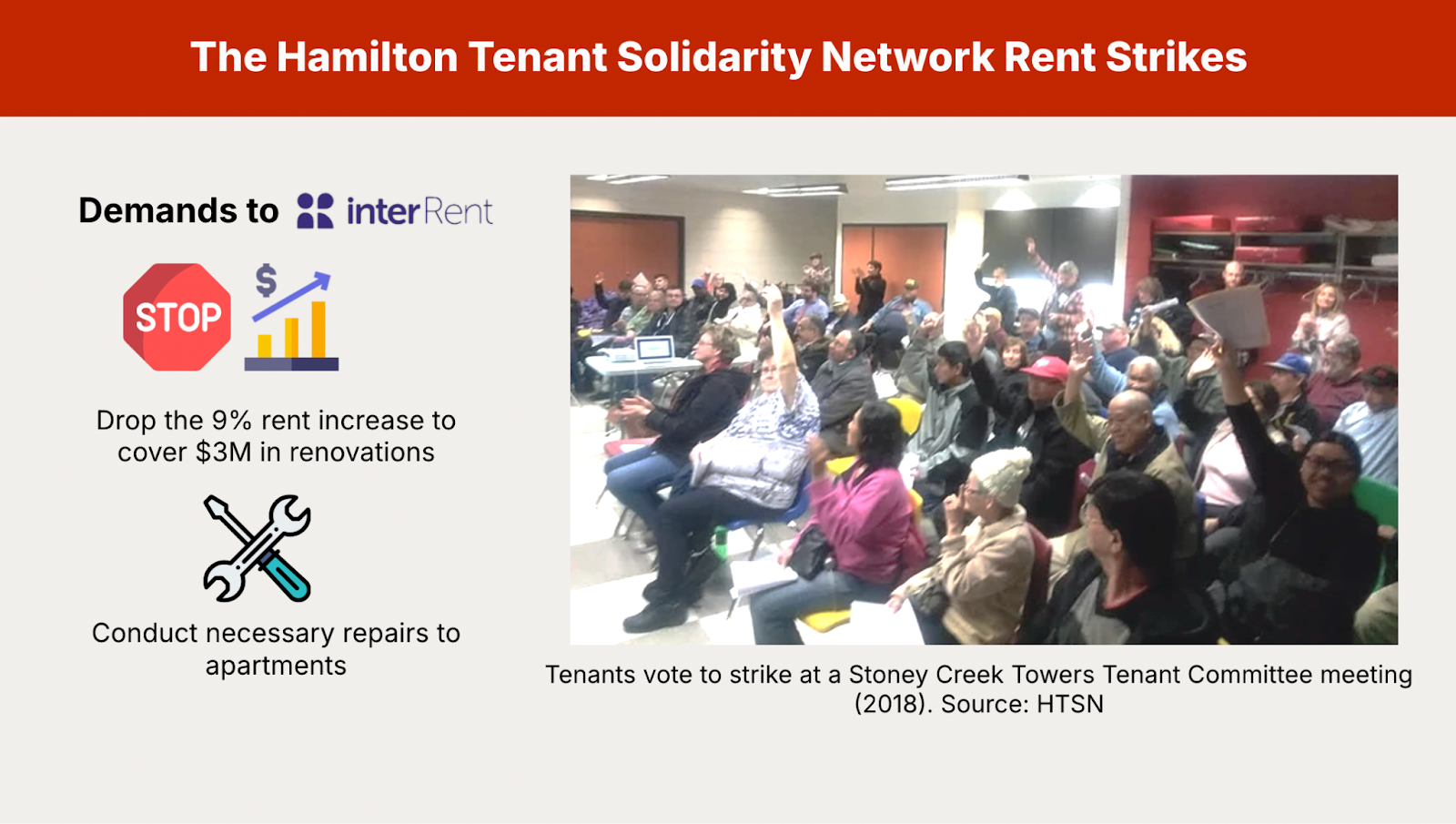

Hamilton Tenants Solidarity Network Organize to Fight InterRent

In this last example, tenants from four apartments in Hamilton, Ontario, launched a seven-month rent strike, in 2018, against their landlord, InterRent—a major Canadian real estate investment trust (REIT) . The strike demanded that InterRent:

- Withdraw its application for a 9% rent increase (6% above the legal annual limit of 3%), and

- Complete long-overdue repairs to tenants’ apartments.

InterRent, originally founded in Ontario, has continued to expand westward. To date, this REIT has acquired five buildings in Marpole: 8675 French Street, 8735 Selkirk Street, 1373 West 73rd Avenue, 8740 Cartier Street, and 8790 Cartier Street.

The Hamilton Tenants Solidarity Network (HTSN) was formed in 2015 to build working-class neighbourhood power. Like the Metrotown campaign, The HTSN door knocked, held meetings to vote on and plan the rent strike, and trained tenants who eventually led the movement.

By the end of the 7-month strike, the tenants won the necessary repairs to the apartments, but they were not able to fight off the 9% rent increase.

Reflecting on this partial loss, the HTSN identified a few key challenges. First, tenants and organizers were not united on their strategy to fight against InterRent, underestimating the stakes of going up against a REIT. They did not anticipate InterRent to spend tens of thousands of dollars to suppress their campaign instead of accepting the tenants’ demands (the cheaper option). Secondly, InterRent made note of who was striking, and staggered their delivery of rent increase notices to tenants. This tactic caused a rift in the tenants’ collectivity and sowed division.

With these examples in mind…

What are the lessons to be learned from these past movements?

The past policy changes won by tenants show us that fights are necessary for us to change our conditions. With class struggle as our focus, we need a strategy that educates, organizes and unites people of this neighbourhood to fight against the ruling class.

We are in a much better position now because of those who fought before us. We can learn from their wins and losses as we build neighbourhood power and take our homes back from the ruling class to have it under our control instead.

It Is Not Enough To Fight Injustices as they Occur, We Need a Long-Term Vision

In these three examples, people fought back when faced with immediate changes to their conditions — rent increases in the 1970 and Hamilton campaigns, and demo-victions in the Metrotown campaign.

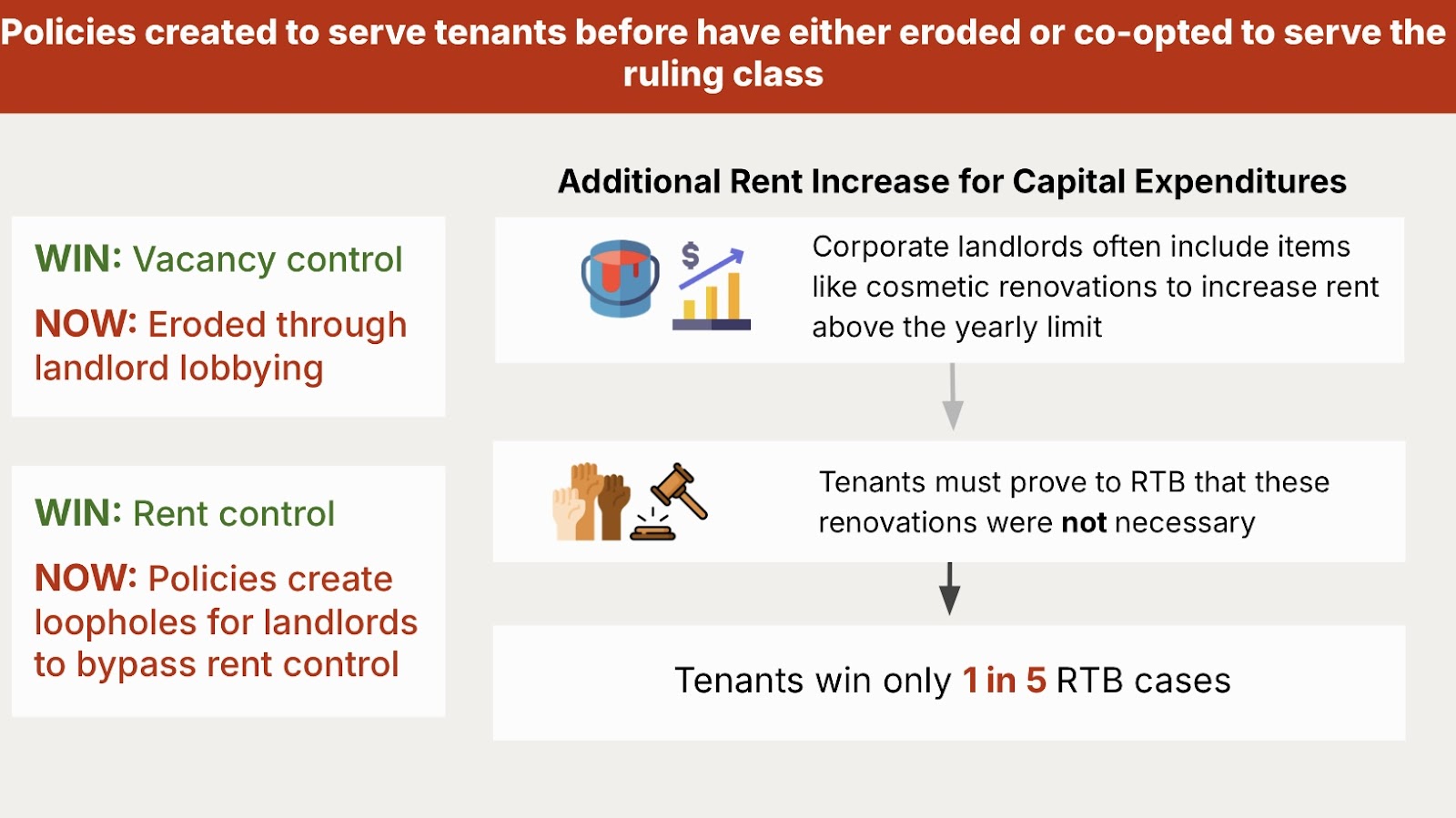

However; it is not enough to respond to injustices as they occur. Many policies that were won through these past campaigns, created to serve tenants, have either eroded or been co-opted to serve the ruling class.

First, vacancy control from the 1970s tenant movement has been completely eroded by landlord lobbying. Nowadays, once a tenant moves out (or is evicted), landlords can increase rent for the next tenant with no restrictions. We see this often being used today as an excuse for landlords to evict tenants, to charge higher rent for their next tenant.

Rent control, which was also introduced in the 1970s – restricts landlords to increase rent only once a year. Today, rent is restricted to roughly 3% increase per year, but policies have sprouted over time that provide loopholes for landlords to raise rents above the allotted 3% increase (like we saw in the Hamilton case).

Tenants who challenge a rent increase generally have little chance of defeating rent increases in courts — only 1 in 5 cases brought to the RTB favour tenants. This is an example of how tenants fought for, and won, the RTB as a protective body, but the RTB has been co-opted to now mostly serve the ruling class.

Defining the housing struggle as a class struggle helps us point to the ‘big picture’ enemy

We must organize as the working class, not as a “tenant class.” Framing our struggle as tenants vs. landlords may lead us to mistakenly identify all landlords—including working-class homeowners who rent out their basement suites—as the primary enemy. However, our enemies are not other working class people trying to survive under the same system.

Instead, we must unite and fight against the luxury developers who systematically displace people to build condos that most cannot afford, the financialized landlords who, despite COVID-19 causing increased rates of homelessness, profited massively off the housing market that year, and the government who encourages these parasites to flourish.

We are in a much better position now because of the people who have fought before us. Their work are lessons that will guide us as we build the neighbourhood power we need to take our homes back from the ruling class and have it under our control instead.

Leave a comment